Juan had originally published this article on 3 May 2012 on the blog IdeasdePapel

Every year since 1982, with February, March and April on the horizon, talks, publications and debates about the Falklands conflict arise. War memories and suffering crowd the headlines of newspapers, veterans are remembered, strategies of war and decisions taken are revisited, documentaries are broadcasted, and today and yesterday’s political speeches analysed. Some bring back the humiliation of a lost war and the pain of broken families; others talk about what happened, what did not happen and what could have happened of an unnecessary and stupid war, like all wars.

Now then, and without wanting to elude the events of 1982, why is it that every time we talk about the Falklands we do it, almost instinctively, with reference to the war? Having talked with different people; Argentines and British, young and old, women and men, I feel there is something of an untold truth. A fixed and implicit debate from which we, the people are left out.

We are neither asked how we feel nor how we identify ourselves with the Islands. Neither school, nor media, nor patriotic discourses seem to examine the Islands’ history, geography, industry or resources. What happened in the Falklands between 1833 and 1982? What was done or said about it then? And before? How many of us actually know that the Islands have only one city, Stanley/Puerto Argentino, and that half of the Islands’ population are soldiers?

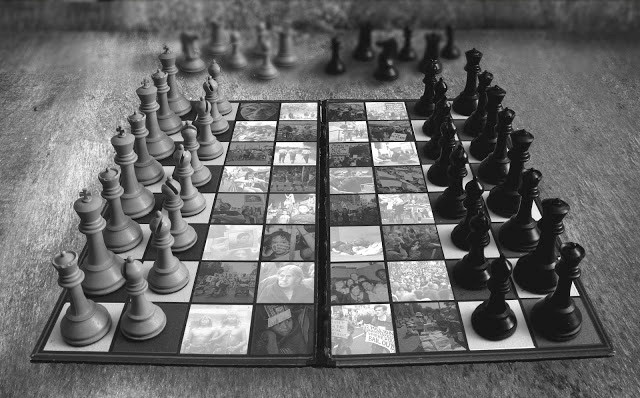

The Falklands make me think of a game of Chess. Whatever our nationality or sentiments on the issue, we do not participate in this game but rather prostrate flat to become the board. A board tiled with people in black and white, so close yet so far, watching how the game is played. Yet, this is a strange game; the rules seem to have changed. Some pieces appear right before us, on the board, while others have been left out. Kings, queens, and bishops, political and military leaders, agents of discourse and masters of information; they play the game for us from both ends and they, with greater or lesser impact according to their assets and strategy, monopolize every action and decision, even when we think of the Falklands.

Kings and queens on one side of the board, on one side of the Ocean claim for the political sovereignty of the Islands arguing the archipelago is part of Argentine continental shelf, integral and indivisible part of our territory belonging to the Province of Tierra del Fuego, Antarctica and Islands of the South Atlantic. On the other side, kings and queens of the United Kingdom first circumvent any mention of the issue, typical English strategy of impenetrability and self-restraint; it is out of the equation to put into question the sovereignty of British overseas territories! No, Sir! – Unquestioned debates, screaming silences which read some English sensationalist headlines and reveal the chronometrically measured appearances of the members of Parliament. They then assert the inalienable right to self-determination of the people, their people, the Falklanders.

At both sides of the board, the bishops are the chiefs of knowledge; they wield with talent these claims only to portray them as essential elements of our identity. Like brooms, bishops sweep the dust of internal social problems, of insecurity, of unemployment, of poverty and corruption under the carpets of ‘identity’ and ‘motherland’. Like vacuum cleaners, bishops take pains to shut us out; everything is silence and omission, no questions asked, nobody is asked. There is neither debate nor anything to debate. If we dare pose questions, they make sure we get the message: Asshole! The Islands’ sovereignty can’t be questioned! Las Malvinas son Argentinas! On the other side, the message sounds different, somewhat more…moderate and short, with less passion yet with the same missive, ‘no questions asked’: There is nothing to discuss, the Islands are British territory and their inhabitants are and declare themselves British. They, the bishops, decide the when, the how and the why when it is talked, written or when we are instructed about the ‘Falklands issue’.

When I listen to these clouts of arguments and platitudes we are told, once and again, in the press, in the radio, in television, I feel they think we are stupid. They piss on us without even having the courtesy to call it rain. With any luck they might give me an umbrella, but I’m afraid they believe I won’t realise or that I won’t care. They water down opium and give it us pretending we get high.

I believe that behind these annually orchestrated diplomatic upsurges and political backfire, and this year more than others, the issue is all about political and economic interests that seek to cover up other problems rather more pressing to our realities, to our day to day lives. Rooks, knights and pawns, there are so many things we don’t think of and leave off the board…

Rooks; citizenship of production, communication and integration. Have we been asked, Argentines, whether we agree or not with the economic blockade of the Falklands to gain a reaction from Great Britain? What consequences could this bring for Argentina and the region? Rather than wanting to force, to no avail, the reaction of a deaf parliamentary monarchy still anchored in its imperialist pride and 19th century nostalgia, would it not be better to integrate the Islands? To integrate them economically in order to promote trade, industry and tourism within the region? Castling, it’s through the exchange and compromise of bishops and rooks, of representatives and citizens, and not their isolation, that we achieve the communication and links necessaries to reach an agreement, a plan. If we truly care about the Islands, as passionately and hysterically portrayed by our bishops, have we been asked, have we asked ourselves what to do with the Falklands in case of reaching an agreement over their sovereignty with Great Britain? And with the people who inhabit them today? What shall we do with them; kick them out, integrate them, kill them? Without rooks there is no castling.

Knights; nature, soil, resources. Argentines, why do we hear so much about the sovereignty of a couple of islands which at this moment, and though it upsets us, we DON’T have, and why do we hear so little, or nothing, about the desertification, depopulation and appalling lack of development of our Patagonia which we DO have? English and Argentines, why are so many discourses, energy, lobbying and research spent towards the archipelago’s gas and petroleum? Fuels that today are technologically unreachable, will be spent with the mere effort to extract them and, anyway, we already have somewhere else?

Pawns; of people, identity, social realities, priorities and truth. English, and Kelpers, have you been taught, or are taught at school that the Falklands war had little to do with the Falklands, its sovereignty and the right to self-determination of its inhabitants? Do you know the war had much to do, instead, with the political audacity of parliamentary representatives who knew how to capture the feeling of frustration and nostalgia of a slowly crumbling empire with the decolonization first, with the depression of ’70s after? English, and Kelpers, in times of rising unemployment and of social cuts to education, cuts to pensions, cuts to the welfare state, are you given any explanation about the costs involved in maintaining a permanent military operations base in the South Atlantic?

Argentines, why are we told about the ‘militarisation’ of the Falklands when since 1982 half of the population are soldiers? The British soldiers, with their ships and machines of destruction, did not arrive after Christmas 2011, they have always been there. Argentines, do we presently care about the islands in these times of ever increasing inflation, of insecurity in the streets, of poverty in the north, of complete discrimination and marginalisation of land rights and deprivation of social justice of those few indigenous people who still live in the Chaco, Cuyo, and southwest regions of Argentina? How important can the Falklands be when the cemetery of its fallen heroes, young conscripts dressed up in fear and uniform, is left in oblivion? Is it worth blocking the only route, Santiago-Stanley/Puerto Argentino, through which the families and friends visit the fallen?

At the point of finishing this article, it is already May and I no longer see in Argentina chronicles of the war or effusive speeches claiming back the Falklands’ sovereignty, and if they still exist they are not in the front covers…in their place now figures the conflict with Spain over YPF… In England, the issue and the responses to the diplomatic turmoil were always treated with manners of omission; this can’t be questioned, and later with hypocrisy: At least hypocrisy is what cries out loud in my mind when I hear a former empire and parliamentary monarchy, the United Kingdom, criticising the imperialist attitude of a former colony and democratic republic, Argentina.

In any case, the heated diplomatic exercises did not go beyond the 30th anniversary of the war, last April 2. It is time to stop being a board, let’s cease to be afraid. Let’s escape the silence and fear to express ourselves. Let’s make questions, let’s put the missing pieces on the board and balance the game. Let’s create a real debate, with more dialogue and less discourse. A debate in which we participate; in which our realities, our worries, our identity as people are represented. After all, it is very difficult to reach an agreement and solve a conflict like the Falklands without informing and listening to all the parties involved, without being listened to, without talking to each other. It is as difficult as to finish a chess game without rooks, knights and pawns.

*This is a translation from the original article in Spanish: Falklands Islas Malvinas: Un partido de reyes, reinas y alfiles. Special thanks to Gabelo, my friend, for the photography work and to Chidoro!, my dad, for his drawings.